SPOKANE, Wash. — It was considered the “Mount Everest” of cold cases.

Investigators in Washington have used genetic genealogy to link one of three now-deceased brothers to the 62-year-old murder of a girl who vanished while selling Camp Fire mints.

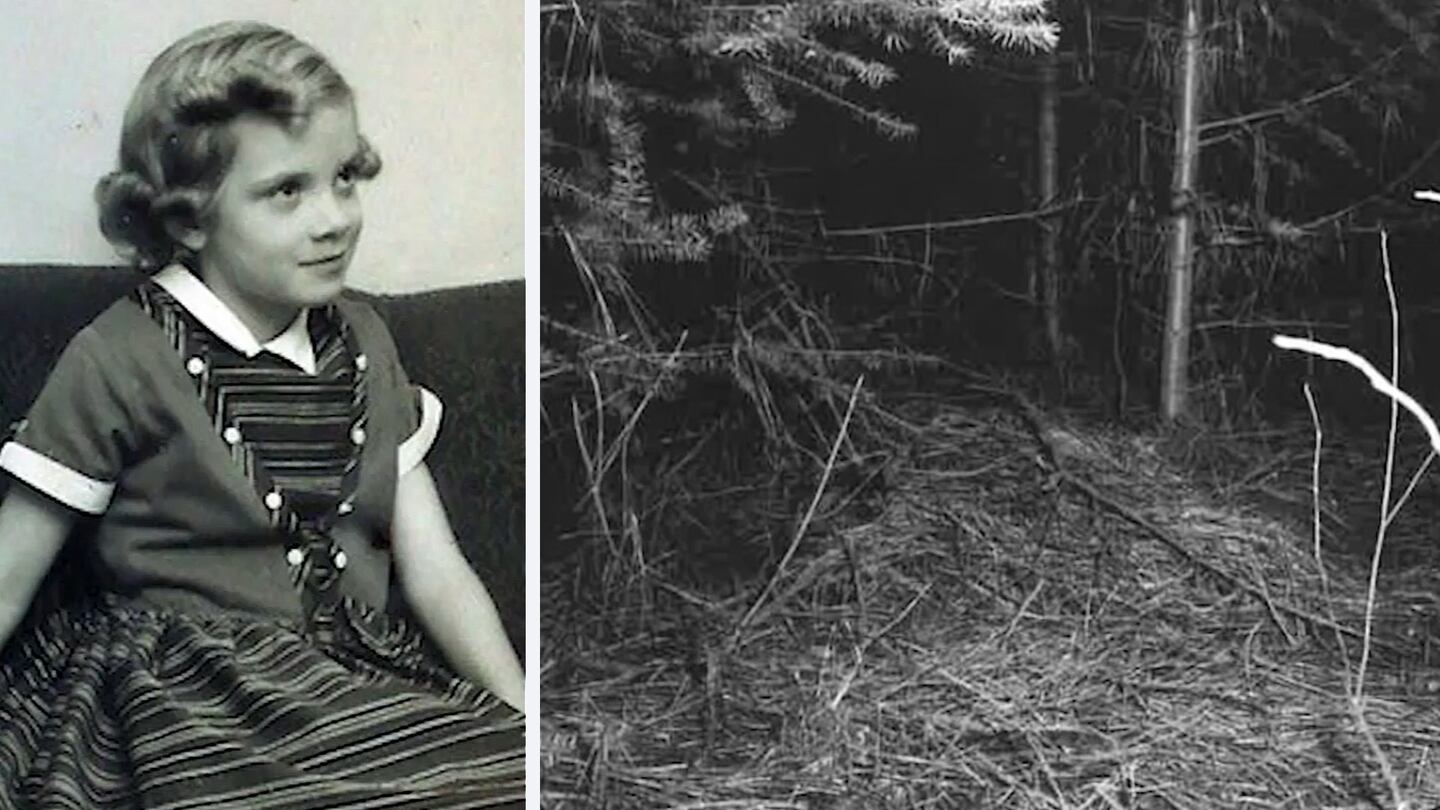

The body of 9-year-old Candice Elaine Rogers was found March 22, 1959, in a wooded area near Spokane. The heartbreaking discovery ended an intensive 16-day search that resulted in a helicopter crash that killed three U.S. Air Force airmen.

>> Related story: 1980 Texas ‘Jane Doe’ identified as missing Minnesota teen

The search has continued, however, for the person responsible for raping and strangling the girl, who was known to loved ones as “Candy.”

Spokane police officials last week announced that the search for Candy’s killer was finally over. According to authorities, DNA evidence submitted to a company that specializes in genetic genealogy led cold case detectives to three brothers, all of whom are now dead.

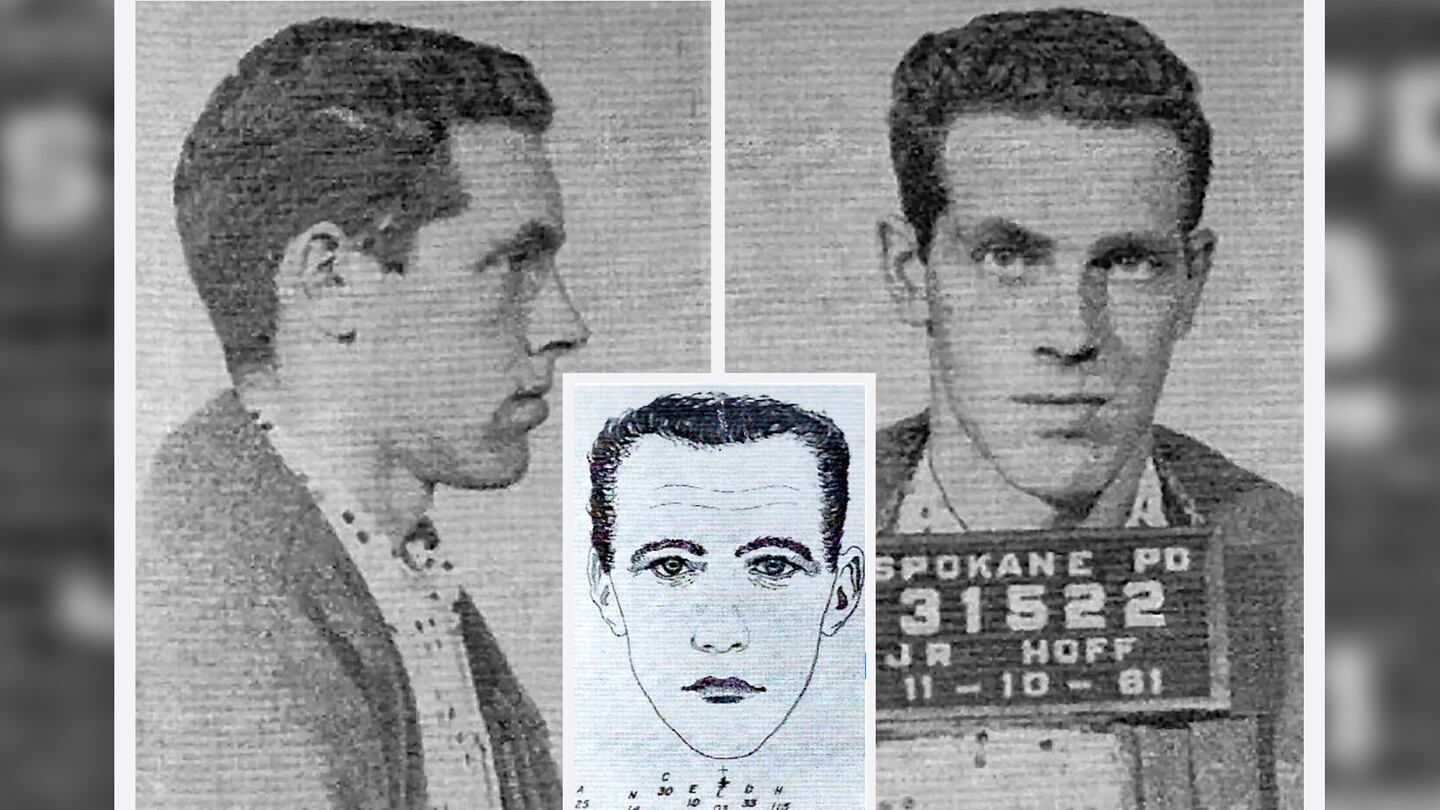

The genetic profile linked one of the men, John Reigh Hoff, to Candy’s murder.

“The scientific evidence conclusively indicated the DNA sample collected from Candy’s clothing was that of John Reigh Hoff,” a police statement said. “The DNA findings, coupled with corroborating evidence, allowed the investigators to determine John Reigh Hoff was responsible for the rape and murder of 9-year-old Candy Rogers.”

Hoff, who was 20 at the time of the homicide, lived about a mile from Candy and her family. A native of Spokane, he had entered the U.S. Army at age 17 and was stationed at missile sites surrounding the nearby Fairchild Air Force Base, according to police.

Hoff was kicked out of the Army following a 1961 assault conviction. In that case, Hoff assaulted a woman, forcibly removed her clothes, tied her up with her own clothes and choked her before fleeing. The woman survived, and Hoff served six months in jail.

He died by suicide in 1970 at the age of 31.

It was unclear if Hoff knew Candy, but Spokane police Sgt. Zac Storment said Friday that Hoff’s stepsister, who was 10 at the time of the murder, had served as Candy’s “big sister” in the Camp Fire program.

Storment said cold case detectives would not have been able to solve the case without the diligence of the original investigators, who preserved vital biological evidence long before DNA technology was established as a crime-fighting tool.

“We are very fortunate that the detectives that came before us and everyone that handled that evidence did a good job preserving it, so that we could be where we are today,” Storment said in a video released by authorities.

Looking for Candy

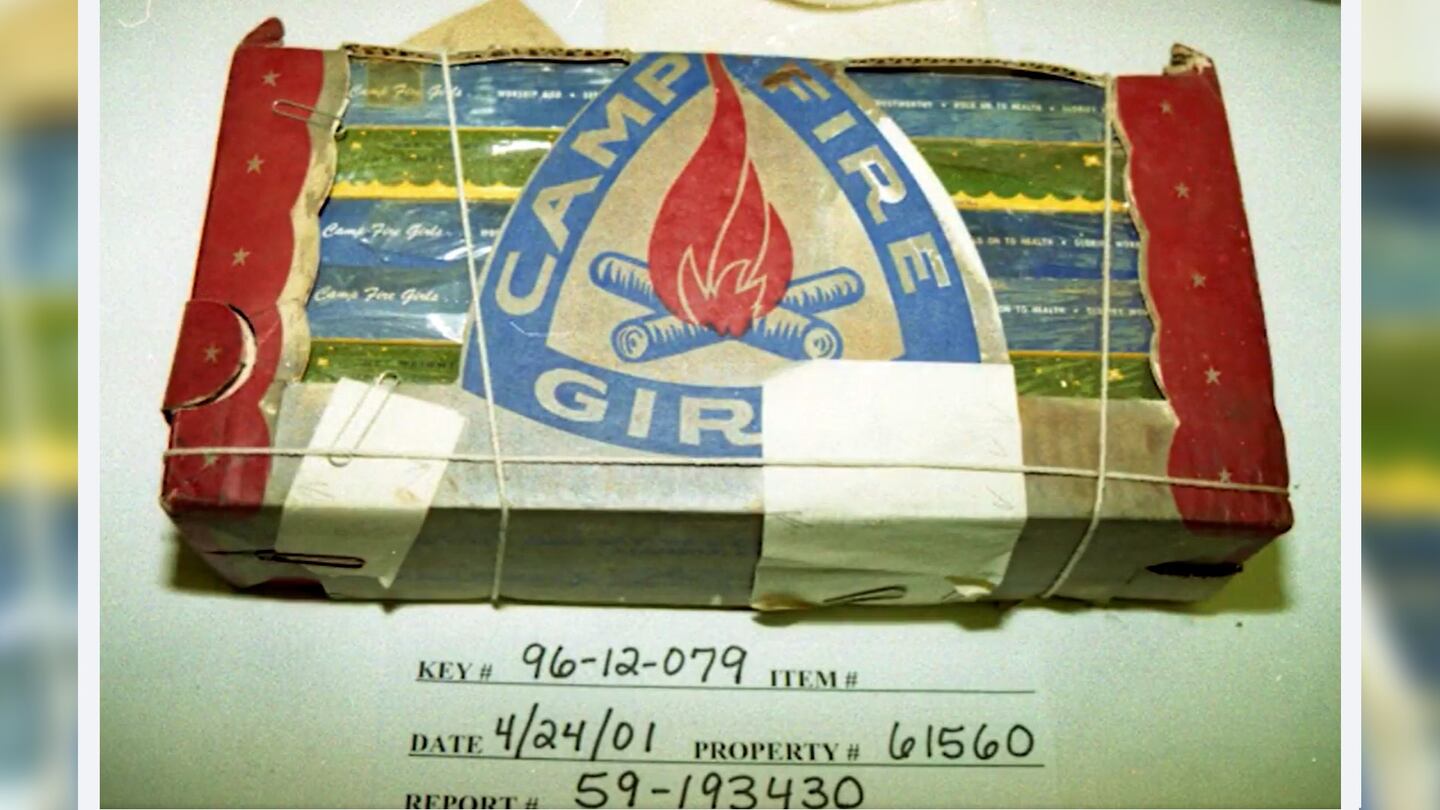

On March 6, 1959, Candy returned from school, played with her beloved dog and ate a cookie, according to The New York Times. She then set out from her family’s West Central home to sell mints for the Camp Fire Girls. Candy was a Bluebird, or part of the youngest age group in the organization.

When Candy, an only child, failed to come home, her mother grew worried.

“That angst intensified as Candy remained missing into the evening, and soon every available police officer as well as citizens and other organizations joined in the search,” a Spokane police statement said. “At a time with no cellphones, GPS or security cameras, investigators had very little to go on.”

Candy’s boxes of Camp Fire mints were found strewn along Pettet Drive, appearing to head away from the neighborhood. The girl, however, was nowhere to be found.

Over the next two weeks, more than 1,200 searchers scoured the area for the missing child. The day after Candy vanished, a helicopter being used in the search struck high-tension power lines and crashed into the Spokane River.

Three Air Force airmen, Airman Marlice D. Ray, Staff Sgt. William A. McDonnell, and Lt. Kenneth G. Fauteck, were killed in the crash, according to police. Two men survived.

It was another pair of airmen who stumbled upon a pair of girl’s shoes two weeks later while hunting in a wooded area about 7 miles from Candy’s home.

“On their return to the base they continued to talk about their discovery and wondered if the shoes could be related to the search for Candy,” the police statement said. “They reported their findings, and as daylight broke the next morning, a search party descended on the area.”

Minutes into the search, Candy’s body was discovered under a shallow layer of brush and pine needles, police said.

The girl had been sexually assaulted, and her killer used strips of her own clothing to bind her and strangle her, detectives said.

In the months following Candy’s murder, detectives pored over thousands of tips and leads but got nowhere.

“In 1959, there was no registered sex offender program, but individuals with similar criminal histories were contacted,” authorities said. “Several suspects were developed, but police weren’t able to get enough evidence to make an arrest.

“Months turned to years, and frustrated yet determined detectives continued to work on the case but kept running into dead ends.”

Meanwhile, Candy’s clothing and other evidence sat in storage, waiting for science to catch up.

The ‘Mount Everest’ of cold cases

As longtime detectives retired and new ones took their place over the years, the Candy Rogers case remained on the shelf. The little girl was never far from investigators’ minds, however.

“I keep saying it was the Mount Everest of cold cases, the one we could never seem to overcome,” Storment said. “But at the same time, we never forgot.”

Earlier this year, detectives working with the Washington State Police crime lab learned of genetic genealogy, a relatively new technique in which a genetic profile obtained from DNA evidence is compared to thousands of profiles uploaded into public genealogy databases.

If authorities obtain a familial match, forensic genealogists use the data and other public records to create a family tree, and subsequently, a list of potential suspects.

Storment took a DNA sample from semen left on Candy’s body and submitted it to Texas-based Othram Inc., one of several genetic genealogy companies that have emerged over the past few years to aid law enforcement agencies.

Othram’s scientists were able to narrow down the suspect pool to three men: Hoff and his two brothers.

“They did an incredible job getting it down to a small group,” Storment said.

Watch Friday’s news conference below.

All three men are now dead, and John Hoff was the only brother to have children.

“Investigators contacted the daughter of John Reigh Hoff, and upon learning the nature of the inquiry, she dropped everything and met with detectives,” the police statement said.

The woman submitted a sample of her own DNA for analysis. The testing showed that she was 2.9 million times more likely than someone from the general population to be related to Candy’s killer.

Detectives needed to be sure they had identified the right man, however.

“SPD investigators requested and were granted a warrant allowing them to exhume the body of Hoff and collect sample DNA,” according to police.

Hoff, who was buried in the same cemetery as Candy, was exhumed and a DNA sample was taken.

Testing showed that his genetic profile matched that of the semen found on the slain girl’s body, authorities said.

Storment said while the news was a relief to Candy’s few remaining relatives, it was a devastating blow to Hoff’s widow and children.

“I took those people’s lives, and their childhood, and dumped it on its head,” the sergeant said Friday at a news conference. “What they believed about their father and their growing up has been forever changed.”

Hoff’s daughter, identified by police only as Cathie, was 9 years old when her father died — the same age as Candy when she was murdered. Cathie said in a police video that learning about her father’s alleged past was shocking.

>> Read more true crime stories

It took a while for the disbelief to ease and the reality of the crime to sink in, she said. She’s been left with sadness and anger over his actions.

“It’s just really sad to find out that someone — not even just your dad, but just someone in your family — could do something like that,” she said.

She and her siblings had grown up believing their father had killed himself because of depression.

“And now I think, ‘No, he was evil,’” Cathie said. “It wasn’t an escape, in a way, from it, but he got to die with people thinking he was an upstanding man. And he wasn’t.”

When Hoff’s body was reinterred following the exhumation, his family had him reburied in a different cemetery from that of his victim.

Candy’s cousins told Spokane police that the tragedy of her death was made worse by the fact that her mother and grandparents died not knowing who killed the little girl.

“I feel like Candy’s loss was just a horrible loss,” a cousin said tearfully. “She was so cute. And she didn’t have much time.”

©2021 Cox Media Group