BOSTON — Health care workers on the front lines of the coronavirus response have been working harder than anyone else during the pandemic.

As more cases surge and people continue to die from the virus, many doctors and nurses who are overloaded with patients to care for say now they have to start preparing to make some difficult decisions as the situation escalates.

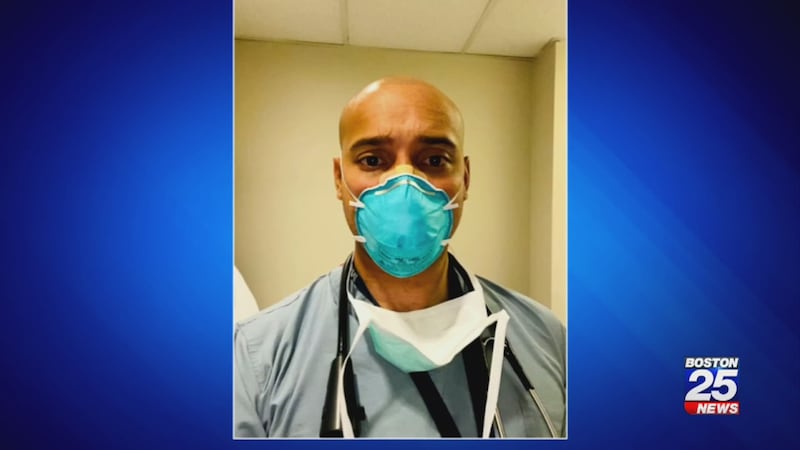

Alister Martin, an emergency room doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital, tweeted in frustration last week after he opened up about having to put 12 patients on ventilators in just one shift.

“These are such higher volumes than we have ever seen - our baseline is usually 2-3 patients a day and now we are seeing a tremendous increase in patients being put on ventilators, its really really unprecedented, a huge surge,” he tweeted.

Putting a patient on a ventilator is hard work and it requires more than just the manpower to do it - patients must be heavily medicated during the process and there is a concern over a shortage of the drugs needed.

“To get someone on ventilator we need to do couple things - one is sedating them, two is paralyzing them,” said Martin. “The medications we use to do that are in short supply, just in the last few months we have seen a 50 percent increase nationwide in the orders or request for sedatives and paralytics. So, we are getting more creative as providers. Luckily, we were trained for this, it’s not just about plan A and B anymore, we need to be thinking plan D, E, and F if we get to the point in time when we don’t have these medications."

Martin also weighed in on the effects ethnicity and economic disparity has on the number of people contracting the virus.

“Just here at my hospital, at Mass. General, nearly 50 percent of patients who have COVID-19 are Hispanic,” said Martin. “There are a lot of different reasons [for that], first of all its harder to get tested when you live in a poor community. Our initial testing requirements were so strict we couldn’t really decide who had COVID-19 and who didn’t, so were missing a lot of cases. Number 2, when you live in poverty its hard to tell people to do the things we are telling them to do like self-isolate or quarantine. Just last week I had a patient who is a young mom of three kids who lives with her elderly mom in a one bedroom in Dorchester. She said, ‘Doctor, how am I supposed to self isolate?’”

The state Department of Health recently came out with guidelines for deciding who gets a ventilator. Essentially, it asks doctors to give patients a score that includes their past medical history to weigh whether they will have a higher chance of surviving the virus and thus should be given a ventilator. Martin has since voiced his opposition to the idea.

“What we’re talking about is a nightmare scenario and all of us hope we never ever have to enact this crisis of care first of all,” said Martin. “Here’s the deal, number one all patients get a score when they come in with COVID-19 symptoms. Number two, the higher the score the less likely you are to get a ventilator or critical care resources. The diseases that give you points, looking at things like diabetes, kidney disease, heart diseases, etc. all of these diseases are found in higher rates in communities of color.”

Martin believes the guidelines need to be updated to reflect a fairer selection process. New York, on the other hand, only considers who is most likely to survive the current illness.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

“I’m confident the government and the really smart team of people he has at DPH he has around them are going to take another look at the guidelines,” said Martin."We have to update them to include this to from a more inclusive lens of health equity."

Moving forward, Martin’s biggest concern is that they will have to start enacting these crisis standards of care, where they’ll have “to make the decision on who lives and who doesn’t, who gets ventilators and who doesn’t.”

“I am also concerned that because of this crisis we may vacate our values,” said Martin. “We talk about caring for the vulnerable and making sure we do our best to give patients a fair shot, but my concern is that we may leave those values behind temporarily. I am most hopeful because of the decisions we have to make - we will choose to really show what we are made of and we will decide to put our values first and take care of people when they need to be.”

Related stories:

- AG investigating Holyoke Soldiers’ Home stricken by virus

- Some health care workers demanding Baker tighten COVID-19 restrictions

- Harvard Medical student translating COVID-19 information into 37 languages to help non-English speakers

- Nurses calling hotels home while fighting on the front lines of pandemic

- He set up over 100 tablets to donate to hospitals so patients can see families virtually

Read more local coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

© 2020 Cox Media Group