Mass- — “This isn’t acceptable for a child – so why is it acceptable for the elderly?”

That’s one of many questions Crystal Johnson has about her mother’s care at Sterling Village nursing home in central Massachusetts.

In March 2020, her mom, Donna, entered the for-profit Sterling Village after suffering a stroke while battling Alzheimer’s.

At the time, the state was under severe COVID-19 restrictions.

“And we couldn’t get into that building at all,” Johnson said.

The family’s only visits were through windows or outdoors.

“We just thought everything was perfect,” Johnson said. “They just told us what we wanted to hear.”

By January 2021, Donna’s health was failing.

She was admitted to a hospital for testing. Crystal says that’s when her family got a call from a hospital doctor.

“She came in with some severe injuries, cracked ribs, internal bleeding,” Johnson said. “Her sodium was 167, which means she was severely dehydrated, a black ulcer on her back, just these big toenails this long.”

Sterling Village didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment, including phone calls left with staff. Johnson’s family filed a complaint with the Department of Public Health, which told them they found no deficiencies.

INSPECTION DELAYS ENDANGERING RESIDENTS

According to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, state surveyors inspect nursing homes “at least every 9-15 months to assess compliance with federal standards of care.”

Those federal standards include “staffing, quality of care, and cleanliness of facilities.”

Inspections include interviews with residents, examinations of medical records and review of policies and procedures.

Routine recertification surveys are crucial – they form the basis of the federal government’s ranking of nursing homes from one to five stars.

The state can also launch unannounced, on-site investigations in response to concerns and complaints about resident care and safety.

The federal government halted routine inspections temporarily in March 2020 at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic – which created a backlog.

By mid-August 2020, the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that States could resume all routine inspections.

Massachusetts has since reduced its backlog by 84%, according to Department of Public Health spokesperson Olivia James.

The state didn’t provide additional details about Massachusetts’ backlog.

But 25 Investigates’ analysis of federal CMS data finds that MA is still behind many other states when it comes to catching up with routine nursing home recertification inspections.

25 Investigates found 32 nursing homes in Massachusetts still haven’t had a recertification survey since 2019.

Sterling Village has had an even longer wait: state inspectors haven’t conducted a recertification survey of Sterling Village since 2018.

A recent Senate committee report found 14 nursing homes in five states — Idaho, North Carolina, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Oregon — lacked a recertification survey since 2018.

And of those 14 nursing homes, four facilities had a 1-star rating.

In contrast, Sterling Village has a four out of 5 star rating.

“The staffing shortages and inspection delays endanger nursing home residents,” reads the report.

State Sen. Mark Montigny, a Democrat of New Bedford who chairs the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Healthcare, said the state’s falling short of its responsibility to hold nursing homes accountable.

“A great failure for a long time,” Montigny said. “They absolutely have failed Massachusetts families and they’re failing them until it’s fixed.”

HIGH CASELOADS

Identifying trouble spots falls on the shoulders of the Department of Public Health’s 82 surveyors that have to inspect about 41,300 nursing home beds, according to the Senate committee report.

That’s a rate of 504 beds per surveyor.

Massachusetts surveyors have the 14th highest caseloads in the country, according to a new report by the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging.

That’s the highest rate in New England.

And it’s far below states like California, which has 654 surveyors for its roughly 114,000 nursing home beds.

The report found state nursing home inspectors are also facing the crunch of having to undertake additional COVID-19 inspections amid the pandemic.

Massachusetts had a relatively low rate of vacant surveyor positions: 4% in 2022, down from 14% in 2002.

But 48% of nursing home surveyors in Massachusetts have two years or less experience as of 2022, up from just 16% in 2002.

Delays in routine surveys can mean it’s tougher for people to have the most up-to-date picture of the quality and safety of a nursing home they’re considering for themselves or a loved one, according to the Senate committee report.

“Survey delays limit the information available to the public to make informed decisions on nursing home care for themselves and their families,” the report reads. “In some cases, CMS’ Care Compare website relies on survey results from as early as 2015, diminishing the timeliness and accuracy of information marketed to consumers as a quick reference to evaluate facility quality.”

Nationwide, 1,523 nursing homes haven’t had a standard survey since March 18, 2020, according to the Senate report.

In Brockton, the for-profit Guardian Center nursing home hasn’t had a recertification survey since June 2019.

Since then, the nursing home has racked up roughly $230,000 in penalties for failure to adhere to federal standards for nursing home patient safety and care.

But when people look up the Guardian Center on the federal CMS Care Compare website, they’ll see the nursing home still has a four-star rating.

Inspectors found a resident at the Guardian Center fell and suffered a right arm fracture in August 2020, when an unassisted aide used a slide board to move the resident from the wheelchair to a bed – against the resident’s plan of care.

That’s according to inspection reports obtained by 25 Investigates through a public records request.

Representatives of the Guardian Center didn’t respond to a request for comment left through the nursing home’s website.

The Department of Public Health did not make a representative available for an interview despite repeated requests for an interview by 25 Investigates. A spokesperson said Tuesday that “staff are unavailable for an interview.”

25 Investigates asked DPH about the lagging inspections and the high case load rate.

A spokesperson said Tuesday they are working on responses to questions, including if the state plans to conduct a recertification inspection of Sterling Village soon, whether Massachusetts needs more nursing home inspectors and how many fines that the state has levied in fines against nursing homes in the past.

Sen. Montigny said he wants answers from the Department of Public Health about the delayed inspections.

“They should come to us and ask for more money and they should stand on the rooftops screaming and yelling,” Montigny said. “If it’s resources, it’s also leadership or lack thereof, as it has not had great leadership more recently. You know, and if they want to claim it’s a lack of resources, then say it. Stop worrying about who you’ll offend.”

INCREASED ENFORCEMENT

Lawmakers this year are considering numerous bills to address systemic issues concerning nursing homes – from enforcement, to staffing, to higher penalties.

New Attorney General Andrea Joy Campbell, a Democrat, is backing a bill to make it easier for her office to pursue enforcement actions against nursing homes who commit abuse and neglect.

“Our state can and should be the leader and the model for the rest of the country when it comes to the issue of elder justice and ensuring that everyone can get access to high quality critical care for their aging family members,” Campbell said.

She’s vowed to launch an Elder Justice Unit in her office whose work will include investigating nursing home neglect and abuse.

The attorney general’s office has announced several settlements with nursing homes over the last year.

Last May, then-Attorney General Gov. Maura Healey, a Democrat, announced an over $250,000 settlement with five nursing homes to resolve allegations of patient neglect, insufficient staff training and inadequate care.

In December, her office announced a $1.75 million settlement with a Connecticut-based long-term care management company over allegations of failing to meet the needs of residents with substance use disorder.

The governor’s proposed budget includes funding for an inspection team for all healthcare facilities, including nursing homes.

‘WORSE THAN EVER’

But Montigny said that despite the spotlight created during the pandemic – Massachusetts nursing homes are in crisis throughout the system.

“Lots of attention, more money, more investigations, even criminal,” Montigny said. “But at the end of the day, you still have a bunch of really lousy nursing homes still operating.”

“In some ways, I think it’s worse than ever,” Sen. Montigny said.

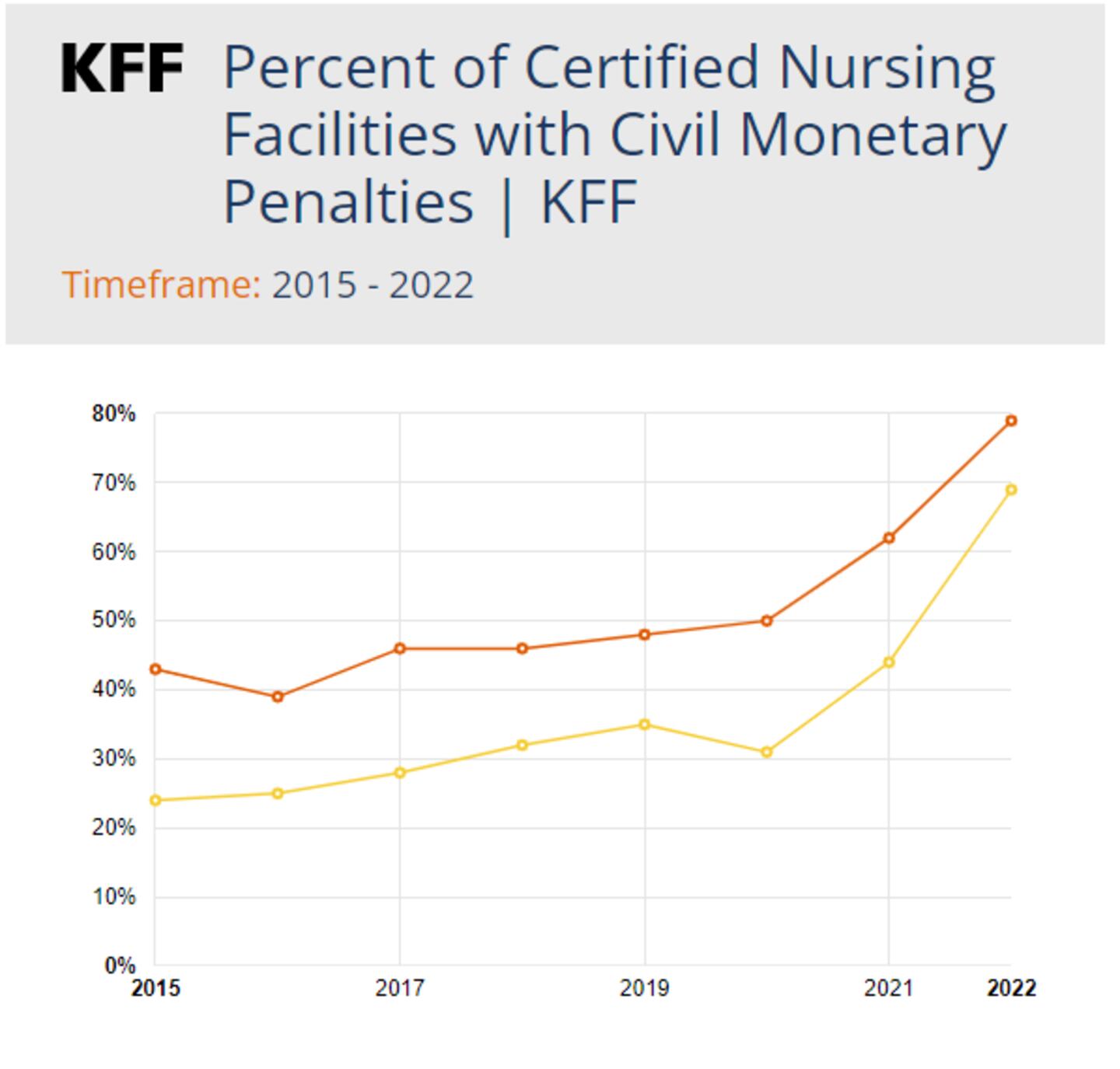

Massachusetts has often had a higher rate of nursing homes with civil monetary penalties than the nation as a whole.

For example, in 2020, half of Massachusetts nursing homes had civil monetary penalties.

That’s far above the national average of 31%.

Montigny said the Senate report highlights the urgent need for the government to amp up enforcement of nursing homes: from inspections, to increased fines.

Following inspections by state surveyors, nursing homes can face fines levied by the federal U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Fines are often aimed at getting nursing homes to change behavior – nursing homes can get the government to reduce fines if they fix issues raised by inspectors, for example.

Montigny said federal fines aren’t high enough to compel nursing homes into investing more into care.

“You are not fining at a level that hurts and possibly forces the corporate entity to change hands,” he said.

States can also levy fines – but MA’s fine for violations of nursing home standards is just $50 a day.

Montigny said lagging inspections and paltry fines means it’s hard to address systemic issues, and that nursing homes can continue to see fines year-after-year with seemingly little resolution.

“There are absolutely good nursing homes,” Montigny said. “But why are we allowing the bad, why are we allowing the mediocre? It’s hard to lose your license.”

Montigny has filed legislation to increase the state fines to up to $23,000 per day, matching federal standards.

25 Investigates asked DPH how often it uses fines against nursing homes.

Montigny said the state fines lack enough teeth.

“Nowhere near enough,” he said. “The state fine is a joke. I’m embarrassed to tell you it’s $50 a day.”

AG Campbell said she also wants to increase the maximum civil penalty for mistreatment, abuse or neglect of an elderly patient that leads to injury or death to $250,000, up from $50,000 currently.

“It’s critically important if we want to really get accountability when there’s wrongdoing,” Campbell said during an April legislative hearing. “The penalties must be strengthened so that they reflect the severity of the offenses, so the AG”s office can hold bad actors accountable, truly accountable. So we can send a clear and resounding message to the industry that this type of conduct won’t be tolerated.”

That legislation would “massively” increase penalties against nursing homes, according to Tara Gregorio, president of the MA Senior Care Association, which represents 325 long-term care facilities statewide.

Leaders of nursing homes have often stressed that funding is the main issue impacting quality and care.

“We believe strongly that those funds should go right back into quality improvement and workforce,” she told lawmakers at an April legislative hearing.

Gregorio also wants lawmakers to expand and make permanent a revolving fund to provide no-interest forgivable loans to help nursing homes impose, modernize and update facilities and provide residents with single rooms.

“There was an overwhelming number of worthy applications, but the funding could not support those all,” she said.

Frank Romano, whose family owns several for-profit nursing homes in Massachusetts, told lawmakers he received four grants from $25 million in nursing home improvement funds: three for dialysis equipment and one for air quality equipment.

Gregorio said MassHealth underfunds the cost of care by at least $27 per day, resulting in an annual funding gap of $200 million.

She said her group’s backing legislation aimed at closing that gap, increasing wages for aides and allowing CNAs to dispense non-narcotic medications to residents.

But Montigny said he questions why there’s such a large swath of for-profit nursing homes if the industry is truly so unprofitable.

About 71% of MA nursing homes are for-profit, while 28% are non-profit, according to KFF.

“The industry comes in and very effectively lobbies for higher rates with no restrictions, no training, no review, no investigations, and no incentive really to put the mediocre out of business, which means more of a pot to pay more money for quality care,” Montigny said.

The MA Senior Care Association reported spending $302,500 on lobbying expenses in 2022 alone, according to state lobbying disclosures reviewed by 25 Investigates.

Two associations representing nursing homes throughout Massachusetts – Massachusetts Senior Care Association and LeadingAge MA – both declined repeated requests for interview from Boston 25.

STERLING VILLAGE FINES

Hundreds of nursing homes across Massachusetts have paid more than $29 million in fines for failing to meet federal quality standards over the past decade.

That’s according to 25 Investigates’ analysis of ten years of enforcement data obtained through a public records request to U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Sterling Village has faced $95,200 in net federal fines over the past decade, according to 25 Investigates’ analysis of CMS data.

Sterling Village is far from among the most fined of the over 350 nursing homes in Massachusetts.

But Montigny said in general, fines can be too low to spur nursing homes to make change.

In 2022 alone, the average annual cost of nursing home care for a semi-private room Massachusetts exceeded $151,000, according to a report by Genworth Financial.

Sterling Village last had a full recertification inspection in 2018.

But since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the nursing home along with thousands nationwide have faced targeted inspections that specifically look at infection control practices.

In 2020, inspectors uncovered multiple instances of failure to follow basic infection control protocols at Sterling Village, according to inspection data obtained by 25 Investigates through a Freedom of Information Act request.

In November 2020, inspectors said that Sterling Village failed to ensure staff followed infection control measures, including proper use of PPE and cohorting residents based on COVID-19 status.

Staff didn’t use proper PPE for a resident on quarantine from a recent hospital admission – all in front of the inspector.

“CNA #1 entered the room without donning a gown or gloves,” the survey reads.

The inspectors found another resident who was on quarantine after readmission from a hospital was placed on quarantine with a resident who never had COVID-19 before.

“During an interview on 11/10/20 at 3:00 P.M., the administrator said there had been a breakdown in communication amongst staff,” reads the inspection. “She said Resident #2 and Resident #3 should not have been placed in the same room.”

Inspectors also found the nursing home failed to test residents for COVID-19 after a staff member tested positive.

“Further review indicated one unit’s negative residents had not been tested and none of the residents’ facility wide who had been recovered for greater than 90 days had been tested, as required.,” reads the inspection.

‘WHAT HAPPENED?’

Crystal Johnson’s mother Donna was 72 when she died in January 2021.

Johnson said she never got records from Sterling Village nursing home about what happened to her mom. She’s instead had to rely on the hospital records, including results of the autopsy.

“What happened?” she said. “How did these things happen? Why is there no documentation?”

Johnson said she’s concerned about how nursing homes have avoided liability amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Massachusetts, like many other states, passed laws in April 2020 that protected nursing homes and hospitals from lawsuits except in extreme cases involving “gross negligence.”

That law ended in June 2021.

“Bed sores, that’s straight neglect,” Johnson said of her mother’s bed sores.

Johnson said her family reached out to the Department of Public Health, but said they found no deficiencies. 25 Investigates reviewed the Johnson family’s complaint.

Johnson’s family still has questions about how Donna spent her final months: including why her mother had cracked ribs and restraint marks on her paralyzed side.

Johnson said she doesn’t understand why her mother was restrained.

Donna herself worked for years as a certified nursing aide in nursing homes.

“She treated the residents like they were family,” she said. “This is very sad how she was living her last year of her life.”

Johnson also wants Congress to pass a law ensuring loved ones who follow infection control protocols can visit nursing home residents in future pandemics.

“I feel like it’s not talked about enough and the care of elderly and what happens to our loved ones in these places,” Johnson said.

“This could be your mom, your grandmother, your aunt, your sister,” she said. “And that’s the care we want?”

This is a developing story. Check back for updates as more information becomes available.

Download the FREE Boston 25 News app for breaking news alerts.

Follow Boston 25 News on Facebook and Twitter. | Watch Boston 25 News NOW

©2023 Cox Media Group