LISBON, Portugal — A small country, a world away from Boston, is winning the war on drugs.

Just 15 years ago, Portugal was a much different place than it is today. It was hard to miss the people dying from heroin overdoses like what we see all over the United States.

Portugal is roughly the same geographic size of Maine, but with more than 10 million people living there. That’s about the same as the populations of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont and Maine combined.

According to the latest statistics from the Centers for Disease Control, opioids killed more than 42,000 people in 2016. That’s more than any year on record – and it’s still rising.

In Massachusetts alone, nearly 2,000 people died from overdosing on opioids.

Like many communities in the U.S., Portugal seemed like a haven for heroin addicts, but now it is surviving the opioid epidemic.

The rate of deaths from opioid overdoses has dropped by about 90 percent in the last decade.

Could the Portugal Solution work here?

The Portugal Solution

Lisbon, the country’s capital, is one of the world’s oldest cities. It is the soul of a country rich in history.

Boston 25 News visited the bustling city to find out more about the programs and decisions that brought its life and energy back from the brink.

Dr. Joao Goulao is part of what has changed the country. He’s the national coordinator for drugs and drug addiction.

“It was dramatic,” he explained of the heroin problem. “We had a drug overdose every single day at that time.”

Goulao and his team sought out help in the public health area and focused on ways to treat the drug problems, but also to prevent them.

“Everything based on that we’re dealing with a health condition and not a criminal one,” he said. “Consequently, we proposed the decriminalization of drug use.”

It was a dramatic shift in thinking: decriminalizing drugs.

“It is still forbidden,” he noted. “We have still administrative sanctions for drug users. We compare it to using the seat belt. It’s designed to protect you, but if a police officer sees you not using it, he stops you.

He may impose a fine, he may have you attend a course for drivers, but you don’t get the criminal record that stigmatizes you for the rest of your life. You don’t end up in jail.”

“The problem with decriminalizing is that people mix it up with regulation or legalizing.”

— Nuno Capaz – Lisbon Dissuasion Commission

Instead of going to jail, you end up before a committee at the health department that decides what kind of treatment or medical help you need. There is a sanction along with the public disapproval of it, but little involvement from police unless you’re trafficking drugs.

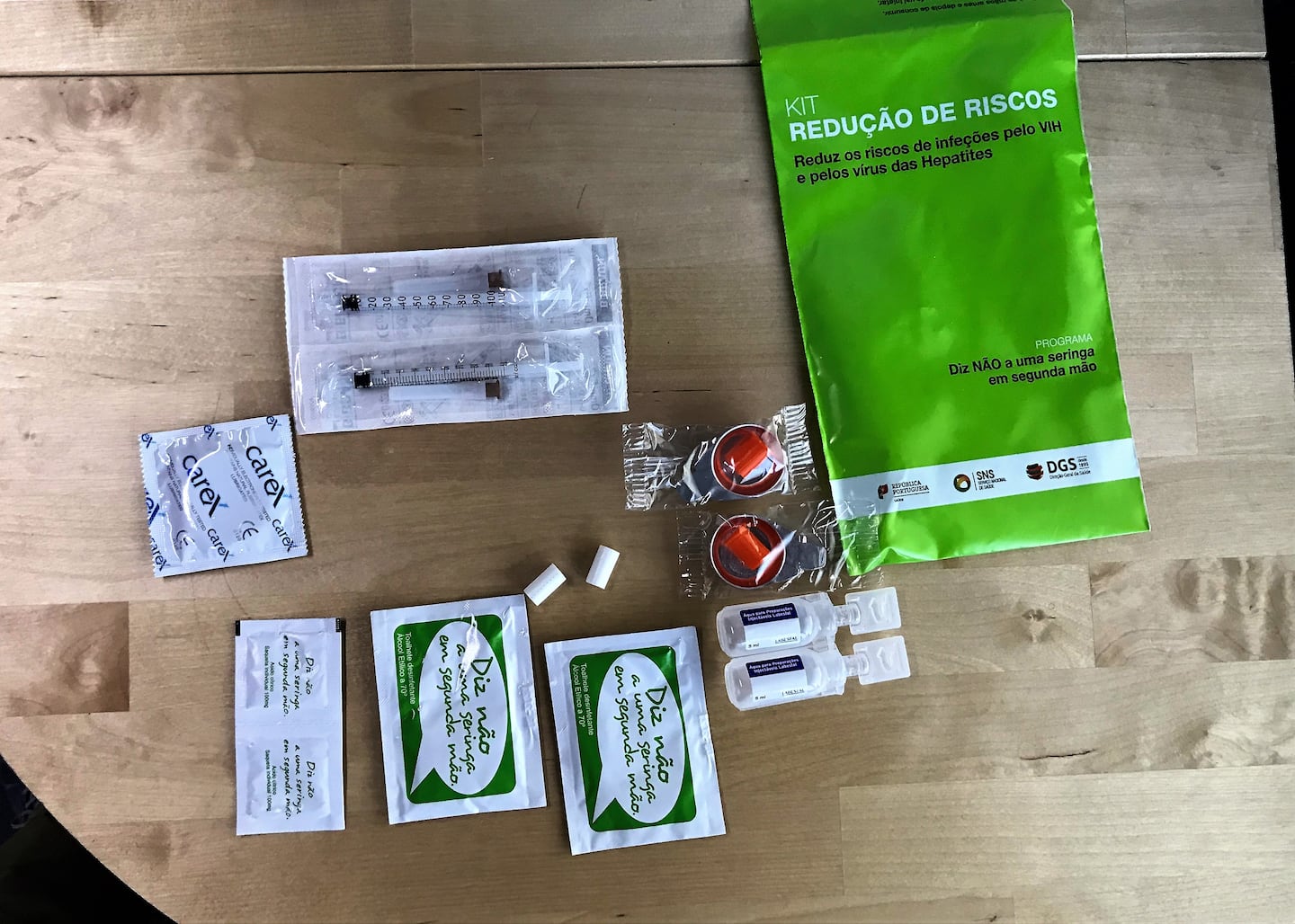

The treatments are wide ranging and easily available in neighborhoods as officials showed us.

Dr. Goulau said there was initial push back from lawmakers, but not the public.

“Common people were very much in favor of the idea because everyone could say it was difficult to find a Portuguese family without problems,” he said. “So, there was a very good acceptance of the idea of decriminalizing and turning this into something with this approach. At the political level, things were a bit more complicated.”

Politicians weren’t eager to make these dramatic changes. But since then, there’s been a huge drop in overdose deaths. There were hundreds of deaths a year when this program started, but a decade later, in 2016, just 27 people died from overdosing on heroin.

“We’ve had good results in all of the indicators. Of course, we haven’t solved the drug problems in our country, but we have what we feel are the tools to deal with the new challenges as they show,” Dr. Goulao said. “I think the use of new opioids is spreading and very present in [the U.S.] and other places like Canada. It has something to do with the culture of prescription opioids and the pressure from pharmaceutical companies.”

Stories of Survival

On the streets of Lisbon, there are countless heartbreaking stories, but in the end, most are stories of survival.

Rue Coltaz started using heroin at just 13 years old.

He said he had just turned 13 and was offered heroin at school. It evolved to smoking heroin after injuring his leg and he’s been addicted ever since.

But then something changed, and Rue sought help through one of Portugal’s government treatment programs. For him, this has been the answer: a methadone van that offers a substitute for heroin.

Methadone is a medication often used to help people withdraw from using heroin.

Rue’s been coming to the van every day for the past ten years.

“It feels like nothing [to take it]. Nothing at all,” he told Boston 25 News. “[Without it] I’d be on that drug today.”

He now has a steady job and says he hasn’t touched heroin in years.

The methadone vans are scattered around Portugal in neighborhoods where demand is high.

Boston 25 News took a ride with a crew or nurses and program workers to learn more about their efforts. The van pulled under an overpass to administer methadone, where people were already waiting for to get their fix of liquid methadone.

“In the right dosage, they can feel as normal as me,” Hugo Faria, one of the coordinators explained.

Two methadone van programs service almost 1,200 people every day in various parts of Lisbon.

We found people come from very different backgrounds. Most walk to the vans, others drive, some walk up during their lunch breaks. Some even showed up driving company vehicles.

“For some of these patients, that’s their routine,” Faria explained. “They want to come take their methadone and go. With these mobile units, we can go to where the drug users are.”

Each patient that shows up to the van is in and out about 45 seconds. Every day in one spot, they treat about 300 people. The patient shows an ID, gets their dosage and then they’re on their way.

Many of the patients didn’t want to be on camera, but Peter Carvalho wasn’t one of them. He shared his story with Boston 25 News, using a translator.

“I started using opium in Afghanistan,” Carvalho said.

He was in Afghanistan as a Portuguese soldier helping U.S. Marines on the front lines of the War on Terror.

“They use opium there to calm the anxiety of the war,” Carvalho explained. “With opium, there’s no anxiety. Ninety percent of the Americans who came, they were also using them.”

He returned to Portugal desperate to find a solution and said this was it.

The methadone van is one of many unique programs that’s worked to nearly eliminate the one-time epidemic.

We also visited a small halfway house on the outskirts of Lisbon, where former drug addicts live to get back on their feet.

David Nolosko has been living in the house for two years. Before that, he says he was clean for 15 years. As he describes it, a fight with his wife put him in a deep spiral involving a list of drugs, but mainly heroin.

“I sold everything that I got. Everything. I had a restaurant, a house, two cars,” he explained. “I’m now starting from zero.”

Nolokos gave us a tour of the drug treatment facility that houses 20 men and one woman. Each has chores around the home.

It’s a very still place, where time almost seems to stop. Everything there has chosen to live there. They’re on a plan that lets them go home to their families on weekends, but then they return during the week to focus on shedding the addiction.

Nolokos admits her may not be ready for that outside world.

“I’m afraid of getting to life again,” he said. “Afraid if something goes wrong. I’m a bit lazy of putting things together to reach the stage that I can be confident it’s the right time. But now I’m feeling more strong and want to go forward with it.”

The programs are working and to top it off, the people using them aren’t paying for it. All the programs are free to those who take advantage and covered by the government.

Could it work in the U.S.?

In Portugal, the burden of fighting opioids doesn’t fall on police.

Instead, it happens in an unassuming building along the streets of Lisbon. There are no signs, not judges and no jails involved.

There is simply a small room on the first floor where those caught using drugs end up.

The first time a person is caught using drugs, they go before the commission and usually are issued a warning. Other cases, however, progress to fines or volunteer hours or attending drug treatment to avoid further sanctions.

If someone is accused of trafficking drugs, police still handle it as a criminal offense.

Nuno Capaz leads the commission. When we sat down with him between hearings, he was adamant about explaining that decriminalizing drugs does not mean legalizing them.

“It’s still illegal. There are sanctions that can be applied to you,” he said. “There’s a legal procedure, but it’s not a criminal procedure. So, people can eventually pay a fine or do community service, but they do not get a criminal record out of this.”

Capaz and his team get about 3,000 cases a year sent to them by police. Across Portugal, there are 19 other commissions just like this one that determine which users are recreational users and which ones are addicts.

There’s a different set of rules for addicts.

“If that person doesn’t comply with any sort of treatment, then we will have to give them sanctions,” Capaz explained. “Anyone found to be an addict must volunteer for treatment.”

He has met with many leaders of foreign countries interested in copying what Portugal has done.

“I think decriminalizing drugs solves one problem and that’s a criminal record,” Capaz said. “That is copy-able anywhere in the world.”

But he doesn’t necessarily think it would work in the United States.

“Because our healthcare system is not the same. Our health care system is basically free for all,” Capaz noted. “I think that in terms of drug policy, the key factor is accessibility to treatment. And accessibility to those sorts of medicines are proven to reduce overdose deaths.”

While at the commission’s office, we ran into a group of criminal justice students from UMass Lowell also learning about Portugal’s version of the war on drugs.

Professor Neil Shortland brought them to see the different approaches.

“For me, I think the bigger takeaway isn’t so much what they think about the problem. So theres’ that shift from a criminal justice world to a healthcare world,” Shortland said.

The students were more blunt, nearly all of them said they knew someone back in New England who had been impacted by drug addiction.

“I think it’s kind of crazy that they hand out the methadone on the streets, because in Massachusetts people aren’t really for helping each other,” Tewksbury native Alyssa Difruscia said. “Here they want people to get better. And that’s why they have these programs. They treat it like a mental disorder instead of a crime.”

The architect of the drug plan in Portugal, Dr. Goulao, believes it could work in New England and the rest of America.

In fact, he was in Cambridge recently to speak at a conference about what the program would take. He was even approached by leaders in Washington to learn about the program in Portugal.

“I had a direct contact from our ambassador,” He said. “President Obama had shown interest in our system.”

But as Dr. Goulao said earlier, it wasn’t convincing the people of Portugal that was difficult, it was getting lawmakers to approve the program.

No Easy Answers

While countries around the world are looking for answers to their problem in Portugal, they aren’t as easy as one might think.

It’s particularly difficult in America, where the overdose problem is only getting worse.

But the question of whether or not it could work here is asked again and again.

Michael Baum, a professor at UMass Dartmouth, has been on long term leave from the school to be in Portugal studying how they’ve made changes.

Baum says he remembers the dark days when the streets were full of addicts.

“It was a public health emergency and that’s how it has been framed here,” he said.

Baum believes Portugal’s solution would work in the United States, but not as a “one size fits all.”

“I’m a believer that it’s really at the state level, I think, in the United States where you have the opportunity for dramatic policy shifts,” Baum said.

Boston 25 News brought what we learned in Portugal to the White House. They were interested in what we found, but said it’s hard to compare Portugal and the United States when it comes to the issue of overdosing on Opioids.

Jack Riley, on the other hand, doesn’t feel that way. He was once the second-in-command at the Drug Enforcement Agency.

“I think it’s something that we could take a harder look at in this country,” Riley said.

He spent 25 years tracking El Chapo, one of the world’ top drug lords. Riley said robust drug enforcement should continue here in the U.S. But he also believes the biggest impact would be expanding the drug court.

“If we did it in areas like Massachusetts or New Hampshire, I really think we could see the fastest improvement in regions by doing that,” Riley said. “The post-arrest way that we deal with addicts and personal users has to fundamentally change if we’re going to make a difference outside the criminal justice system.”

He told Boston 25 News he believes if something doesn’t drastically change, the U.S. will end up back in the 1980s when the focus was more on locking up people and not getting them any help.

While lawmakers may be the key to creating change, many believe it’s an issue that needs to be out of their hands.

“We’re in a very polarized political environment back in the United States, which makes any kind of political consensus difficult — to say the least,” Baum said.

America’s solution is still likely years away, but some believe it may start in a place like Portugal. A bold example for the rest of the world.

Cox Media Group